Danang was a miserable place in early February 1968. It was cold and drizzly. I might as well have flown to a Northern European destination. The streets were deserted, except for military traffic. I had hoped to spend the night on the Helgoland in Danang in order to find out how the ship had fared during the Tet Offensive, and to eat some hearty German food for I was starved. Since leaving Vientiane I had not had a square meal. But the Helgoland wasn’t there. Wisely, the captain had taken her to the safety of international waters.

So I went to the MACV press compound, which lacked charm, but had a passable restaurant and a very good bar. I had a Dry Martini, ate a steak, drank a bottle of wine, took a hot shower, and felt ready for an adventure that afforded me none of these luxuries for a while. It was still dark when I joined a convoy of American Marines early in the morning. I wore two sets of jungle fatigues on top of each other, to which I would add a third before long, and I was grateful for the extra warmth my flak jacket gave me.

Several journalists from the press compound dared the perilous journey by road to the vicinity of the Communist-occupied imperial city. This was our best chance to get there quickly. The cloud ceiling was so low and the security situation around Phú Bài airport so unstable, that we might have had to wait days for a seat on a military flight.

Before we were allowed to board a truck, we were each handed an M-16. “We know that this is against the rules,” a sergeant major explained. He was alluding to the Geneva Convention that stipulated that war correspondents be unarmed. “But,” he added, “We will be traveling through very dangerous terrain and could be ambushed. In that case you will have to defend yourselves. Here’s your choice: carry a gun or stay behind.”

We made it to Phú Bài south of Huế without incident, except for one scene that tickled my sense of irony. Next to me on the back of a truck sat a team of Stern magazine reporters, a photographer and a writer. The photographer was Hilmar Pabel, one of the most celebrated practitioners of his craft in German journalism, and a wonderfully seasoned old trooper. The picture of me on the cover of this book was his handiwork. Hilmar took it during a lull in the fighting in the old city of Huế .

His colleague, though, was another matter. He was a young Austrian writer steeped in the pestilential hard-left stereotypical thinking that poisoned Western Europe’s intellectual life in those days and would culminate in the calamitous May 1968 student uprising in Paris, which in turn infected the entire continent and much of the rest of the western world.

His name was Peter Neuhauser. Aside from his Marxist ideology, he was actually a likable burly fellow, not unlike the leathernecks we traveled with. That’s why they loved him, being oblivious of his pro-Communist views. “You look like one of us. All you need is a haircut,” they said. So when we arrived at the staging area of the Fifth Marines behind Phú Bài Airport, they yanked Peter into a tent, gave him a crew cut, shoved an M-16 in his hands and shouted with glee: “Behold our new gunnery sergeant!” From that moment on they called him “Gunny,” and Peter of all people, pro-Vietcong Peter, seemed to enjoy his new status hugely, which showed in the photographs Hilmar Pabel took of him. This didn’t help his career. The pictures of Neuhauser in a martial pose, along with more pertinent images of Pabel’s films, ended up at Stern magazine’s Hamburg head office a few days later, causing outrage among his peers who failed to see the humor in this. He was never sent on a foreign assignment again.

The next morning, as Peter and I accompanied a battalion of Marines battling its way inch by inch into Huế, he seemed to experience an epiphany of sorts, albeit a brief one. On the road into Vietnam’s former imperial capital we saw scores of dead civilians, individuals and groups, women, old men and children, all elegantly dressed for the New Year. From the position of the bodies we could see that many women had been trying to shield the children with their own bodies against the killers.

“Your Communist buddies did this, Peter!” I told him cruelly.

He went white. “Surely not,” he replied, “These people were killed by American airplanes.”

“No, Peter, this is not what casualties of air raids look like,” I retorted, “Look at these head wounds, look at these body injuries. Look at how some of these women had held up their hands protectively. They were shot at close range. Believe me, I have seen this before: This is the handiwork of killer squads. What we have here is evidence of a war crime. These people were liquidated for whatever crazy reason Communists might have to liquidate women, children and old men.”

Peter Neuhauser fell silent but I knew I hadn’t convinced him; he admitted as much when we next met months later in Hamburg. Neuhauser died a few years later of natural causes, still an unreconstructed leftist. Decades on, I feel occasional pangs of sorrow that even the sight of scores of murdered innocents on the road to Huế had not brought this otherwise pleasant young man to his senses. My days in his company taught me one of the most frightening lessons of this whole Tet episode: nothing, not even the most irrefutable evidence, can trump an ideologue’s fixed ideas.

Phú Bài and Huế are only ten miles apart, but it took us almost a day to reach the MACV compound near the southeastern shore of the misnamed River of Perfumes. Sporadic fighting without air support, due to bad flying conditions, and the need to clear the road of bodies slowed us down. The compound was located in the new European section of the city, an area of broad boulevards with comfortable French villas, a charming Cercle Sportif, or sporting club, and a Cité Universitaire, with 1950s-style apartment buildings for faculty members built in the egregiously ugly 1950s-style of the low-cost housing projects littering the northern outskirts of Paris.

By the time we arrived, the Americans and South Vietnamese had brought this side of town under their control to some extent, at least during the day, while the Old Town with its imperial enclosure, or Purple City, which was patterned after the Forbidden City in Beijing, was still firmly in Communist hands.

The MACV compound consisted of a former hotel with a dining area on the ground floor, officers’ billets on the upper two floors, and an annex with 20 suites. Next to the annex were the so-called hootches: open-bay structures for the enlisted men. The place was teeming with an eclectic assortment of people: military men, journalists, intelligence operatives, aid workers, Vietnamese employees of the Americans and civil servants plus their dependents who had found refuge here from the fighting and from Communist death squads that were still roaming the city looking for supposed counter-revolutionaries to be killed on sight.

“Sorry, guys, all bunks are taken, all blankets too. You gotta make ya’selves comfortable on this here concrete floor,” said the quartermaster sergeant welcoming us to what used to be the dining area. “There are C-rations over there in the corner and lots of paper body bags to keep ya guys warm. Take as many as you want. It’s gonna be cold tonight.”

The compound was closed by nightfall. Nobody could come in, nobody could go out. We heard ferocious battles raging north of the river, but also occasional firefights just outside the compound’s perimeter. I squeezed myself into a narrow space between Vietnamese families, spread out three body bags on the ground in lieu of a mattress, covered myself with three more body bags that were intended to transport fallen soldiers and bore markings showing where the head and the feet were to be placed. I used my knapsack as a pillow. My neighbors spoke French. In whispers they told me how on the day before Tet, Communist death squads had gone from door to door with lists containing the names of people to be tried before so-called people’s tribunals and then summarily killed.

“Do you think the German professors were on those lists?” I asked the man on my right.

“They definitely were, just like the French priests and other foreigners who were also led away,” he replied.

In the middle of the night, bursts of automatic arms fire in our immediate neighborhood woke us: rat-tat-tat, rat-tat-tat, rat-tat-tat, rat-tat-tat, rat-tat-tat.

“Executions,” said the Vietnamese man on my right. “AK-47 Kalashnikov.”

“How do you know?” I asked.

“This has become a familiar noise by now. What you heard was no firefight. These were five volleys from one automatic gun – very purposeful.”

“How close was this?” I asked.

“No more than 100 meters away.”

Forty years later, I befriended in southern California Di Tonthat, a member of Vietnam’s extended imperial family. We discussed the events of Tet 1968 in Huế and discovered that his father, two uncles, and two cousins could have been the victims of this execution. Di’s father, Nguyen Tonthat, had been the mayor of Dalat and later worked as a civil servant at the social security administration in Saigon the offices with which I was familiar; they were next door to the Café La Pagode on Tu Do Street.

In January 1968, Nguyen Tonthat had flown to Huế so spend Tet with his brothers and nephews in their villa. Di and I studied a street map of Hue. “This is where the house was,” he said, pointing to a spot not even 100 yards from the dining area of the MACV compound. “We only recovered the body of one of my uncles. We couldn’t even bury my father.”

Whether I was really an oral witness of their execution or of another murder I shall never know, but that moment stuck in my memory, primarily because it was followed by yet another of my many surreal experiences in Vietnam: something big, warm and quacking crept under my three body bags. It turned out to be a white goose with a yellow beak and grayish-black feathers on its wings. I have always loved geese, especially when roasted and served with red cabbage at Christmas. But I have never had a goose cuddle up to me before, but this one was seriously disturbed. Along with scores of Vietnamese refugees, this frightened bird had fled into the American compound at the beginning of the Tet Offensive and been waddling about the grounds ever since, sometimes inspecting the sleeping quarters. The GIs had named him Garfield. Being a watchful goose, Garfield took up an observation post every night, always at the same place and always looking out toward the street. But when he heard the bursts of gunfire right next door he took fright and sought cover next to me. I shooed him out of our bedroom back to his observation post.

At dawn, we journalists were allowed to leave the compound on condition that we carried an M-16 for our own protection. Peter Neuhauser, Hilmar Pabel and I each accepted one but, at my suggestion, deposited these guns disobediently with the sentry. We were on our way to the kidnapped German doctors’ apartments. “Imagine if we run into a Vietcong patrol carrying arms,” I argued, “We’d be dead. Unarmed, we might at least claim the status of noncombatants, though I am not hopeful that this would mean anything to them.”

Shivering in the cold drizzle, we walked west on Le Loi. This once elegant boulevard seemed deserted and looked in sorry shape. Its villas were pockmarked, its trees felled or mortally wounded. As we approached the Cercle Sportif, where I sometimes had dinner with the German professors, and where Elisabetha Krainick used to swim every day, I was vaguely hoping that a faithful servant might be there to make us coffee but of course this was a foolish thought; there was nobody about – nobody except U.S. Marines racing past us in jeeps and armored vehicles. For a moment the cloud cover lifted, and we glanced across the River of Perfumes. We could see the Vietcong flag – red and blue with a yellow five-pointed star in the center -- flying over the citadel, and we could hear the sounds of furious combat.

The apartment building where the Krainicks lived overlooked the Phú Cam Canal, as did a U.S. tank parked on the estate’s northern flank. Vroom! It fired off a round across the canal. Vroom! The whole building shook as we walked up to the Krainicks’ place on the fourth floor. It had been taken over by an entire platoon of leathernecks and looked in a horrible mess. Clothing, books, scientific papers and private documents were strewn everywhere. To my horror, Peter Neuhauser pilfered through them and slipped some of the Krainicks’ family photographs into his pocket.

“Have you no shame?” I asked him.

“That’s what you have to do if you work for an illustrated magazine,” he replied coolly and left.

The platoon leader was a stocky 23-year old second lieutenant from New Mexico. I knew at first sight that he was a fool, and he spoke like one. He pranced around in a white T-shirt, wearing neither a flak jacket nor a helmet. Vroom! The tank fired off another round.

“What is the tank shooting at?” I asked him.

The lieutenant took me to an open glass door leading to the balcony and pointed at an elaborate French-style villa on the other side of the canal:

“VC snipers,” he said. “They are shooting at us.”

“And you are standing there in a white T-shirt, presenting these guys with a perfect target?”

“Sir, I am a marine, we are trained to fight and die.”

“Doesn’t it cost the American taxpayer $500,000 to train a professional officer?” I challenged him. “Even if you don’t have any fear for your own life, do you really think you should put such a big investment at risk gratuitously? Should you chance leaving your men leaderless?” He stared at me uncomprehending.

As I walked out through the front door and headed down the stairs, I heard a scream the like of which I had never heard before. It didn’t sound human. I turned around. The lieutenant came staggering towards me holding the left side of his chest from which blood spewed. He stumbled, fell, rolled down the stairs and was dead. The snipers had got him.

I walked over to the university hospital where Professor Horst-Günter Krainick, Dr. Raimund Discher, and Dr. Alois Alteköster had worked. It was 75 percent destroyed by the fighting. Seeing my fatigues, most of the Vietnamese civilians avoided my eyes. They were too scared to be seen fraternizing with an “American,” even though a badge on my helmet identified me as a West German journalist: West German, like the doctors who had founded the medical school. They obviously feared that the Communists might return and take revenge on people who had been seen “collaborating” with the enemy – people like me.

An older gentleman quietly pulled me to the side to tell me frightening stories of Kangaroo trials by so-called people’s tribunals. They were set up by the North Vietnamese. The accused were Huế residents belonging to the old aristocracy, the bourgeoisie, and the South Vietnamese civil service, as well as foreigners, active Roman Catholics, priests, in short, anybody suspected of being unfavorably disposed to the revolution.

“They weren’t arrested at random, Monsieur,” he stressed, “Their names were on lists the Communist cadre carried with them. At the tribunals they were not given a chance to defend themselves. They were convicted, taken off and shot.”

“How many?”

“Who can tell? Hundreds? Thousands?”

To this day no precise figure of victims is available. The estimates range from 2,500 to 6,000.

“The worst part of this offensive came when the fighting reached the psychiatric ward,” continued the old man who never gave me his name or position, but he sounded like a French-educated academic. “The patients went wild, running amuck, attacking each other in their confusion. You can’t imagine what it was like. Many died because they were incapable of escaping the crossfire. It was like a scene out of the Inferno in Dante’s Divine Comedy.”

“And where were you at that time?”

“Hiding among the patients, Monsieur, pretending to be one of them, which I wasn’t, but it saved my life.”

He advised me to walk over to the university’s main auditorium, which was crammed with hundreds of homeless people, all still festively clad, all in various stages of bewilderment with blank expressions on their faces; many were injured, with very few nurses or doctors, if any, available to treat them. They had no running water, no electricity, and no sanitation facilities.

I walked quickly back to the MACV compound to telephone my story to my teammate Friedhelm Kemna in Saigon, and to give Baron von Collenberg at the embassy an update about the German doctors. There was only one telephone line out, with a long queue of reporters waiting to put a call through. My turn came after two hours. Then I had to work my way through a succession of military exchanges in the hope that all were staffed by intelligent operators, which they weren’t.

At the top of my voice, I shouted into the field telephone: “Hue, please give me Phu Bai! -- Phu Bai, give me Danang! -- Danang, give me Nha Trang!” -- Nha Trang, give me Qui Nhon! -- Qui Nhon, give me Tan Son Nhut! -- Tan Son Nhut, give me Tiger (the Saigon military exchange)! -- Tiger, give me the PTT! -- PTT, donnez moi l’hôtel Continental, s’il vous plaît.”

After two failed attempts, I finally got through to my hotel, praying that my nemesis, an opium-saturated Indian from Madras, wasn’t on telephone duty that evening. But he was!

“Ici Monsieur Siemon-Netto, donnez moi Monsieur Kemna, s’il vous plaît,” I said: Siemon-Netto here, please give me Mr. Kemna.

“Monsieur Siemon-Netto n’est pas ici,” the opium head answered: he isn’t here.

He hung up!

Thank God, the kindly American colleague behind me in the queue also lived in the Continental and had a copytaker waiting for him there. He dictated his story and then asked his counterpart to keep the line open and fetch Freddy, whose room was on the same floor. So in the end I did manage to give my story to Freddy and ask him to pass on my message to Baron Collenberg.

Then I needed a drink. Thank God, I had a hip flask of whisky in my knapsack. After the grisly experiences of that day, a few gulps from the flask plus some slices of pumpernickel were perfect bliss. Then I had to wait for the American military to move.

The Old City of Huế and its citadel were still in the hands of some 10,000 North Vietnamese soldiers. We were told that the 1st ARVN division, while fighting well, had a hard time trying to move in from the northwest in an effort to retake the citadel, and expected elements of the 1st U.S. Marines division to attack from the southeast. When that happened, I intended to attach myself to one of its platoons.

What happened next was so traumatic that I am left with only fragmentary recollections of the day I joined a Marine platoon as it set out to cross the River of Perfumes at three in the morning. I remember that this unit was unusually large, numbering 53 men. I also remember that its leaders were of a vastly higher caliber than those in charge of the platoon I had met in the Krainicks’ apartment. Sadly, I saw most of them get wounded or killed before the day was out.

I remember us running into house-to-house combat almost from the moment we hit the river’s northern shore. The North Vietnamese seemed extremely well entrenched, firing at us out of every window. I found my story about this battle in the Amsterdam newspaper, De Telegraaf, which was a client of the Springer Foreign News Service. It focused on my most harrowing experience of that day, but one about which I now only have a hazy memory. I was running alongside a black lance corporal. We got pinned down by sniper fire from an upper-floor window and threw ourselves to the ground, with the lance corporal “spraying” the window with volleys from his M-16, to keep the sharpshooter at bay. But then the marine’s gun jammed, as these weapons all too often did in Vietnam. The sniper resumed shooting at us immediately, whereupon the black man lobbed a hand grenade into the window. At once the firing stopped and the lance corporal gave off a whoop.

Next, a woman came out of the door showing the American lance corporal the blood-soaked corpse of a child. He went berserk. “Oh, my God, oh, my God, what have I done? I have killed a little baby! Please help me, God! Oh my God, oh my God!!!” he screamed whirling around like a dervish, while North Vietnamese snipers continued firing at us from the other windows. The platoon sergeant had to subdue his comrade with force and then lead him away from this scene of combat.

It was three in the afternoon when I first found time to look at my watch during a lull in the battle. I turned around: where were all the men I had been with twelve hours earlier? I counted ten, maybe 15. The others had either died or been wounded; another platoon replaced us. It was time for me to get out. I made my way back to the River of Perfumes. Amazingly, the Communists had left the main bridge standing. I walked across it and found myself at a helicopter landing zone (LZ) covered with severely wounded men, hundreds of them, many groaning in agony.

“Major,” I asked him the officer in charge of the LZ, “What’s happening here? Why aren’t these casualties being flown out?”

He pointed at the sky: “Bad flying conditions!”

“But, Major, I have seen worse. The ceiling is high enough,” I protested.

“Yes, but you see, we Marines haven’t got enough helicopters.”

“What about the Army? I have been told that ten miles from here at Phú Bài two Army helicopter battalions are on standby.”

“Sir, we are Marines, we wouldn’t call upon the Army!”

I remember thinking to myself: a maple leaf on the lapel of a major’s uniform is clearly not a certificate of a high IQ. It was time to get out of there. The Theater of the Absurd showed signs of madness here. I had seen the best and the worst of mankind in these few days: heart-rending self-sacrifice and bravery contrasting with the unimaginable cruelty of the Communists and the meat-headed mindlessness of a couple of certifiable halfwits in uniforms.

I remember tears welling up in my eyes thinking of all the dead Vietnamese I had seen in Huế , mostly women and children, and of the maimed young Americans on those stretchers. I had seen them fight so bravely, despite the growing anti-war sentiment in their homeland. I had witnessed the self-sacrifice of so many trying to protect the lives of Vietnamese civilians. And here hundreds of these warriors lay moaning in agony, with nobody giving them the comforting news that they had just vanquished the enemy.

More than half the 80,000 Communist soldiers who participated in the Tet Offensive were killed; the Vietcong infrastructure was smashed. This was a big military victory. It was a hard-won victory for the Allies, but a victory it was. All things being equal, this should have been the Allied triumph bringing this war to a successful end. We combat correspondents could testify to this, irrespective of the pacifist and defeatist spin opinion makers, ideologues and self-styled progressives in the United States and Europe put on this pivotal event. But as I looked at these wounded warriors I feared deep in my heart that in the end their own compatriots might betray them because, as North Vietnamese defense minister Võ Nguyên Giáp had prophesied, democracies are psychologically not equipped to fight a protracted war to a victorious conclusion.

The German national Sunday newspaper, Bild am Sonntag, titled my story from Huế , “Ich habe genug vom Tod,” I have had enough of all that dying. I was anxious to get out of Hue. One look at this LZ told me that I had no hope of getting a ride on a helicopter anytime soon, but I did notice a Vietnamese Navy Landing Craft Utility (LCU) nearby. I rushed over to the vessel, and found its skipper, a Vietnamese naval lieutenant with the leathery complexion of a Comanche chief.

“We are about to sail,” he said, “Welcome to progress: This is the first time since the beginning of the Tet Offensive that an LCU navigates this river. Expect trouble!” We headed east and immediately met small arms fire from the northern shore, a barrage of bullets ricocheting off the ship’s hull. But the vessel continued its journey toward the Tam Giang Lagoon, though I didn’t stay on board long. The shooting subsided as the LCU gathered distance from Huế. I fell asleep. In the middle of the night, the lieutenant shook me and said, “You’d better get off here.” He had stopped at the landing site of a small MACV base on the southern bank of the river.

I don’t remember how I made it from there back to Danang, probably by helicopter. All I know is that I arrived at the press compound a total mess. I hadn’t shaved for eight days. My hands were filthy, my fingers brown from cigarette smoke, and I stank of death and dirt. I can’t even recall if I was hungry or not; my digestive system had completely shut down since leaving this press center more than a week earlier.

I borrowed underwear and a fresh set of fatigues from an American officer and asked one of the compound’s cleaning women to wash my own clothes as quickly as possible. As I showered, dark-grey water came pouring down from my hair and my body. Getting rid of my stubble was the highlight of the day. I went to the bar, had two stiff Dry Martinis but couldn’t eat anything. So I stretched out on my bed and slept for four hours, then wrote my story and phoned it to Freddy in Saigon.

Toward the end of the day, I went over to the Helgoland, which thankfully had returned. The bridge announced that the ship was leaving the pier and asked all visitors to leave. “Stay with us,” the nurses and doctors pleaded with me, “You look dreadful. Have a good meal, have some good drinks, leave the warzone for a night and relax.” The ship’s horn tooted. I couldn’t move, even if I had wanted to. My German friends gave me a very good time in international waters.

These joyful moments didn’t last long. In the morning I returned to the press center. My clothes were back, and I was lucky to catch a helicopter ride back to Hue. In the MACV compound I ran into Peter Braestrup, the Saigon bureau chief of The Washington Post.

“They have found a mass grave,” he said, “We are going there now, why don’t you come with us?” A military truck took us and other correspondents to a site at the southwestern outskirts of Huế that had recently been wrested from Communist control. There were hundreds of women, men and children in that grave, some evidently burned, some clubbed to death, others buried alive, according to a South Vietnamese officer.

“How do we know they were buried alive?” I asked him.

“We found this site when we noticed women’s freshly manicured fingernails sticking out of the ground,” he answered, “These women had been trying to claw there way out of their grave.”

Peter Braestrup thrust his left elbow in my side and pointed to an American television team, a reporter, a cameraman and a soundman, standing aloofly at the gravesite, doing nothing.

“Why don’t you film this?” Peter asked them.

“We are not here to film anti-Communist propaganda,” answered the cameraman.

“This is madness, Peter,” I said, “I have had enough of this for a while.”

“I don’t blame you. We are losing this war after the military had won it. It’s all in the head.”

This was my lucky Huế day. I found a ride to the airport. There was an Air Vietnam DC-6 about to take off for Saigon, and it had a seat for me. Freddy Kemna was anxiously waiting for me at the Continental. He had been a good sport as a placeholder and copytaker, but now he wanted to go to the field himself, meaning the Mekong Delta, with another German correspondent. “I prefer the Delta this time of the year. It’s warmer,” he joked.

It was a Thursday, and I longed for nothing more than Donald Wise’s Stammtisch, the regulars’ table for European correspondents at Aterbea’s, where no one was allowed to speak about the war, about Vietnam, about American politics or anything remotely connected with this whole enterprise.

After the meal, Donald said, “Now that this is over and we can speak about the war again, let me make a suggestion: how about you and I sharing a taxi to take us to the assorted battle fronts right here in Saigon every morning? It’s very expensive because the taxi owner risks having his car blown up. I think it’s worth it. The Americans don’t pay much attention to these small combats because they are mainly Vietnamese operations. But this is nonetheless important.”

So we found a chauffeur with military experience and an air-conditioned Buick. He came by the Continental every morning to take us from one urban battle to the next. One morning we found ourselves in a pitched skirmish at the southeastern outskirts of Saigon where South Vietnamese forces controlled one side of a road and the Vietcong or North Vietnamese the other. There was a burning house to our left. We heard a woman scream, “There’s a little girl in that house! Help!”

We were lying on the ground. Donald rose to his full height of six foot two. He adjusted his helmet and then, with an umbrella dangling from his right arm, walked in measured steps right along the embattled road toward the burning house. Both sides stopped firing. Donald went into the house and came out with the little girl in his arms, his umbrella still dangling. He took her to an ambulance on the ARVN side, handed the child to the driver and said, “Take her to the hospital, my man – take her now!”

Then he threw himself on the ground again and the firing resumed.

We returned to the center of town, had lunch at the Royal and drove to southwestern Saigon where, according to our driver, a fierce house-to-house battle was raging between the Vietcong and South Vietnamese rangers. As we drew closer, we saw the rangers in chaos because they had lost all their officers and senior NCOs. In the midst of this chaos, upright and unperturbed, with his head hanging sideways, walked our colleague Hans von Stockhausen, a German television correspondent.

The tilt of his head dated back to World War II when von Stockhausen was a young major in the cauldron of Stalingrad where he had half his skull shot off; he was the last casualty to be flown out of Stalingrad in a Luftwaffe plane before it fell to the Red Army. Military surgeons replaced the shattered skull bone with a silver plate, which weighed his head heavily to one side. This didn’t stop this good-humored scion of an ancient military family from covering every war he could find as a reporter. Donald Wise nicknamed him thus the galloping major.

“Ah, Herr Vise,” the major shouted, “Zere is no system here, zere is no system here. You vere a field-grade officer, I vas a field-grade officer. Now let’s together bring some system into this mess.”

And so Donald Wise, the former British lieutenant colonel, and Hans von Stockhausen, the former German major, quietly taught the surviving young sergeants and corporals of a South Vietnamese Ranger company how to organize their defenses in house-to-house combat, and before long the battle was over.

Years later, Donald Wise kept reminding me, “I fell in love with the galloping major. What a character! I can’t wait to discuss ‘ze system’ with him again.”

We drove back to the Continental. After a few days, I took the Air Vietnam Caravelle jet home to Hong Kong. Gillian awaited me at Kai Tak Airport. She looked very fetching in her miniskirt showing off her magnificent suntanned tennis player’s legs and flashing me the sweetest smile. She had brought Schnudel on a leash, a native of the New Territories, half chow and half poodle, white and fluffy with a blue tongue. I loved this young dog and his wicked habit of welcoming our female guests -- but only the pretty ones -- with a nip in the rear.

“Let’s celebrate your return with an early dinner at the Peninsula,” Gillian suggested as we got into our red Volkswagen, “I know you are looking forward to a Steak Tartare and a bottle of Australian red.” Gillian’s most wonderful feature is her bubbly personality. She regaled me with hilarious anecdotes from the British Crown Colony’s social scene; I don’t think I had ever enjoyed an evening more than that first one with her after weeks of trauma.

But when we arrived at our apartment on Victoria Peak later in the evening, she abruptly turned serious. Looking me straight in the eyes, she asked, “What is it with you, darling? You seem so distant. You haven’t even embraced me or given me a real kiss. Is everything alright?”

I can’t recall now whether I told her the truth right there and then or a few days later, but eventually I gave her the honest answer: “I haven’t embraced you as I should have, nor have given you a proper kiss because I did not want to defile you. Ever since Huế at Tet I felt desperately dirty.” I was haunted by a sense of dereliction I had never experienced before. For weeks I had the irrepressible urge to take a hot shower and scrub myself several times a day. Now, almost half a century later, I am noticing occasional recurrences of this urge. I attribute these flashbacks to the incontrovertible fact that I am growing old.

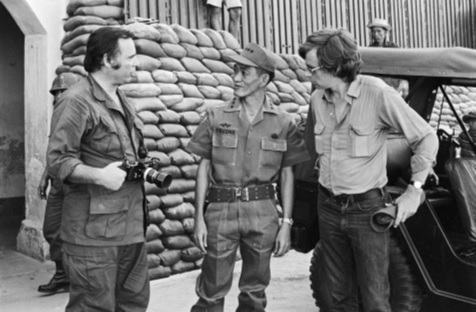

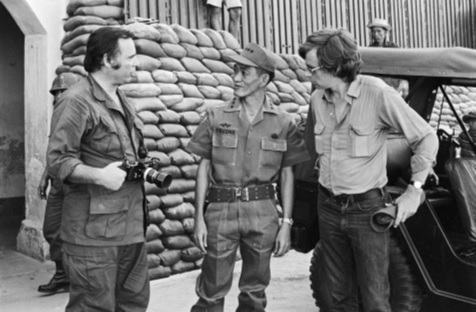

Private collection Kretz

Photographer Perry Kretz (left), General Ngo Quang Truong, commander of I. Corps, and the author during battle for Huế 1972