More than forty years have passed by since I paid Vietnam my farewell visit. In 2015, the world will observe the 40th anniversary of the Communist victory, and many will call it “liberation.” The Huế railway station, where a locomotive and a baggage car left on a symbolic 500-yard journey every morning at eight, no longer qualifies as Theater of the Absurd. It has been attractively restored and painted pink. Once again, as in the days of French dominance, it is the most beautiful station in Indochina, and taxi drivers do not have to wait outside in vain. Ten comfortable trains come through every day, five heading north, five going south. Collectively they are unofficially called Reunification Express. Should I not rejoice? Is this not just as in Germany, where the Berlin Wall and the minefields have gone, and now high speed trains zoom back and forth between the formerly Communist East and the democratic West at speeds up to 200 miles an hour?

Obviously I am glad that the war is over and Vietnam is reunified and prosperous, that the trains are running, and most of the minefields cleared. But this is where the analogy with Germany ends. Germany achieved its unity, in part because the Germans in the Communist East toppled their totalitarian government with peaceful protest and resistance, and in part thanks to the wisdom of international leaders such as Presidents Ronald Reagan and George H.W. Bush, Chancellor Helmut Kohl, and Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, and partly because of the predictable economic collapse of the flawed socialist system in the Soviet Bloc. Nobody died in the process, nobody was tortured, nobody ended up in camps, nobody was forced to flee.

There is an incomprehensible tendency, even among respectable pundits in the West, to refer to the Communist takeover of the South as “liberation.” This begs the question: liberation from what and to what? Was South Vietnam “freed” for the imposition of a totalitarian one-party state that ranks among the world’s worst offenders against the principles of religious liberty, freedom of expression, freedom of speech, freedom of assembly, and freedom of the press? What kind of liberation was this that cost 3.8 million Vietnamese lives between 1955 and 1975 and has forced more than one million Vietnamese to flee their country, not only from the vanquished South, but even from ports in the North, causing between 200,000 and 400,000 of the so-called boat people to drown?

Was it an act of liberation to execute 100,000 South Vietnamese soldiers and officials after the fall of Saigon? Was it meant to be a display of generosity by the victors to herd between one million and 2.5 million South Vietnamese to reeducation camps, where an estimated 165,000 perished and thousands more have sustained lasting brain injuries and mental health problems resulting from torture, according to a study by an international team of scholars led by Harvard psychiatrist Richard F. Molina?

Since the mid-1960s, political and historical mythographers in the West have either naively or dishonestly accepted Hanoi’s line that this conflict was a “People’s War.” Well it was, if one accepts Mao Zedong’s and Vo Nguyen Giap’s interpretation of the term. But the Saxon Genitive implies that a “People’s War” is supposed to be a war of the people. In truth, it wasn’t. Some 3.8 million Vietnamese were killed between 1955 and 1975. Approximately 164,000 South Vietnamese civilians were annihilated in a Communist democide during that same period, according to political scientist Rudolf Joseph Rummel of the University of Hawaii. The Pentagon estimated that 950,000 North Vietnamese and more than 200,000 South Vietnamese soldiers fell in combat, in addition to 58,000 U.S. troops. This was no war of the people; it was a war against the people.

In the all too often hypocritical rhetoric about the Vietnam War over the last 40 years, the key question has gone AWOL, to use a military acronym meaning absent without leave, and the question is: Did the Vietnamese people desire a Communist regime? If so, how was it that nearly one million northerners moved south following the division of their country in 1954, while only about 130,000 Vietminh sympathizers went in the opposite direction?

Who started this war? Were there any South Vietnamese units operating in North Vietnam? No. Did South Vietnamese guerillas cross the 17th parallel to disembowel and hang pro-Communist village chiefs, their wives and children in the northern countryside? No. Did the South Vietnamese regime massacre an entire class of people by the tens of thousands in its territory after 1954 the way the North Vietnamese had liquidated landowners and other potential opponents of their Soviet-style rule? No. Did the South Vietnamese establish a monolithic one-party system? No.

As a German citizen, I had no dog in this fight, as Americans would say. But to paraphrase the Journalists’ Prayer Book, if hardened reporters have a heart at all, mine was, and still is, with the wounded Vietnamese people. It belongs to these sublime women who can often be so blunt and amusing; it belongs to the cerebral and immensely complicated Vietnamese men trying to dream the perfect dream in a Confucian way; to the childlike soldiers going to battle carrying their only possessions – a canary in a cage; to young war widows who had their bodies grotesquely modified just to catch a GI husband and create a new home for their children and perhaps for themselves, rather than face a Communist tyranny; to those urban and rural urchins minding each other and water buffalos. What a hardened heart I had, it belonged to those I saw running away from the butchery and the fighting – always in a southerly direction, but never ever north, until at the very end there was no VC-free square inch to escape to. I saw them slaughtered or buried alive in mass graves, and still have the stench of putrefying corpses in my nostrils.

I wasn’t there when Saigon fell after entire ARVN units, often so maligned in the U.S. media and now abandoned by their American allies, fought on nobly, knowing that they would neither win nor survive this final battle. I was in Paris, mourning, when all this happened, and I wish I could have paid my respects to five South Vietnamese generals before they committed suicide when the game was over that they should have won: Le Van Hung (born 1933), Le Nguyen Vy (born 1933), Nguyen Khoa Nam (born 1927), Tran Van Hai (born 1927) and Pham Van Phu (born 1927).

As I write this epilogue, a fellow journalist and scholar of sorts, a man born in 1975 when Saigon fell, is making a name for himself, pillorying American war crimes in Vietnam. Yes, they deserve to be pilloried. Yes, they were a reality. My Lai was reality; I know, I was at the court martial where Lt. William Calley was found guilty. I know that the body count fetish dreamed up by the warped minds of political and military leaders of the McNamara era in Washington and U.S. headquarters in Saigon cost thousands of innocent civilians their lives.

But no atrocity committed by dysfunctional American or South Vietnamese units ever measured up to the state-ordered carnage inflicted upon the South Vietnamese in the name of Ho Chi Minh. These crimes his successors will not even acknowledge to this very day because nobody has the guts to ask them: why did your people slaughter all these innocents whom you claimed to have fought to liberate? As a German, I take the liberty of adding a footnote here: why did you murder my friend Hasso Rüdt von Collenberg and the German doctors in Huế? Why did you kidnap those young Knights of Malta volunteers, subjecting some to death in the jungle and others to imprisonment in Hanoi? Why does it not even occur to you to search your conscience regarding these actions, the way thoughtful Americans, while correctly laying claim to have been on the right side in World War II, wrestle with the terrible legacy left by the carpet bombing of residential areas in Germany and the nuclear attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki?

Reminiscing on her ordeal on the Ho Chi Minh Trail in the news magazine Der Spiegel, the West German nurse Monika Schwinn recalled her encounter with North Vietnamese combat units on their way south as one of her most horrifying experiences. She described the intensity of hatred in the facial expressions of these soldiers and wrote that her Vietcong minders had great difficulty preventing them from killing the Germans on the spot. Nobody is born hating. Hate must be taught. Fostering murder in the hearts of young people involved a teaching discipline at which only the school of totalitarianism excels. In his brilliant biography of SS leader Heinrich Himmler, historian Peter Longrich relates that even this founder of this evil force of black-uniformed thugs did not find it easy to make his men overcome natural inhibitions to execute the holocaust (Longerich. Heinrich Himmler. Oxford: 2012). It was the hatred in the eyes of the North Vietnamese killers in Huế that many of the survivors I interviewed considered most haunting. But of course one did have to spend time with them, suffer with them, gain their confidence and speak with them to discover this central element of a human, political and military catastrophe that is still with us four decades later. Opining about it from the ivory towers of a New York television studio or an Ivy League school does not suffice.

In a stirring book about the French Foreign Legion, Paul Bonnecarrère relates the historic meeting between the legendary Col. Pierre Charton and Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap after France’s defeat at Dien Bien Phu (Bonnecarrère. Par le Sang Versé. Paris: 1968). Charton was a prisoner of war in the hands of the Communist Vietminh. Giap came to pay his respects to him but also to gloat. The encounter took place in a classroom in front some 20 students attending a political indoctrination session. The dialogue between the two antagonists went thus:

Giap: “I have defeated you, mon colonel!

Charton: “No you haven’t, mon général. The jungle has defeated us… and the support you have exacted from the civilian population -- by means of terror.”

Vo Nguyen Giap didn’t like this answer, and forbade his students to write it down. But it was the truth, or more precisely: it was half of the truth. The other half was that democracies like the United States seemed indeed politically and psychologically ill equipped to fight a protracted war. This realization, alongside the use of terror tactics, became a pillar of Giap’s strategy. He was right and he won. Even more dangerous totalitarians are taking note today.

To this very day I am haunted by the conclusion I was forced to draw from my Vietnam experience: when a self-indulgent throwaway culture grows tired of sacrifice it becomes capable of discarding everything like a half-eaten donut. It is prepared to dump a people whom it set out to protect. It is even willing to trash the lives, the physical and mental health, the dignity, memory and good name of the young men who were sent to war. This happened in the case of the Vietnam Veterans. The implications of this deficiency endemic in liberal democracies are terrifying because in the end it will demolish their legitimacy and destroy a free society.

However, I must not end my narrative on this dark note. As an observer of history, I know that history, while closed to the past, is always open to the future. As a Christian I know who is the Lord of history. The Communist victory in Vietnam was based on evil foundations: terror, murder and betrayal. Obviously, I do not advocate a resumption of bloodshed to rectify this outcome, even if this were possible. But as an admirer of the resilient Vietnamese people, I know that they will ultimately find the right peaceful means and the leaders to rid themselves of their despots. It might take generations, but it will happen.

In this sense, I will now join the queue of the pedicab drivers outside the Huế railway station where no passenger arrived back in 1972. Where else would my place be? What else do I possess but hope?

Perry Kretz

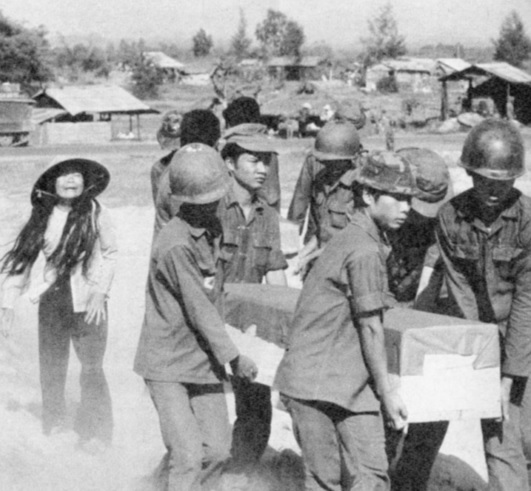

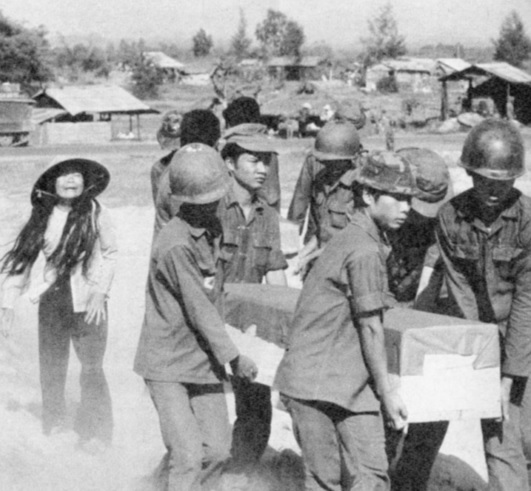

ARVN soldiers bury two young boys killed in a Communist artillery attack on their village near Huế. Their distraught mother has to stay behind because the burial ground is mined.