Tìm Kiếm Bài Đã Đăng

Diễn Đàn Cựu Sinh Viên Quân Y

© 2014

© 2014

Chapter Six

Fundamental analysis

In general, there are two main concepts or "schools" of investing: fundamental analysis and technical analysis. The two approaches are very much different from each other that fervent adherents in both schools simply refuse to admit the validity of the opposing school.

Fundamentalists believe that the market is so efficient that everything, such as news, anticipations, events at a certain point of time has been factored into the stock price. Another way to put it is that the stock market has the ability to discount all the influences on it. So no one can predict the future and the stock market follows a "random walk."

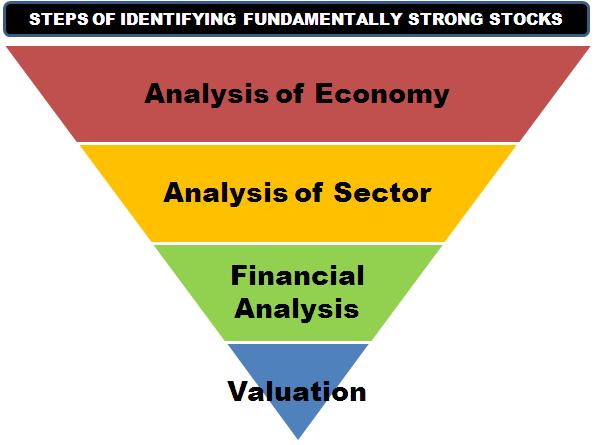

Therefore, the only way to invest soundly into the stock market is to do intensive research topside down from macroeconomics to microeconomics, then focusing on the company. Fundamentalists gather the most information they can about the company, compare them to other companies in the same industry and predict a future "reasonable" target stock price for the company, usually a year ahead. After research, analysts of the fundamental school may issue a recommendation that can be a strong buy, a buy, hold, sell or strong sell for the company.

Technical analysts on the other hand do not care about economics whatsoever. They agree too that the market is efficient and discounts all influences but by the time the investor can figure the reasons why, it is already too late and the market has passed him by.

Furthermore, trying to forecast a stock price by analyzing all the influences is too much work and futile. There are so many economical factors that could influence a stock and no one can properly identify them all. Also, technical analysts, also called chartists because their main tool is only a chart, believe that prices move in trends and history always repeats by itself. Therefore, if an investor can figure out the same patterns that are repeating, he can anticipate the move and get in or out at the right time. This can be called "timing the market."

Although pretty much counter-intuitive because who in their right minds want to invest into a company which they know nothing about it, the technical analysis approach has an advantage of self-fulfilling prophecy. Too many investors believe in it and therefore, they sell or buy in mass when they see signals on their charts.

Obviously, a combined approach of fundamental and technical analysis makes sense greatly. The common way is to use fundamental analysis to select a stock and then use charts (or technical analysis) to pick the right time to get in or out the market.

On this chapter we will deal with some of the most basic concepts of fundamental analysis.

Fundamental analysis refers to the research of company financial statements, its management and competitive advantages, and its environmental analysis. When applying to stocks, fundamental analysis aims to answer the vital question of “how to pick a winner.” Fundamental analysis is based on the concept that the market may misprice temporarily a stock and in the long run the correct price will eventually be reached. A savvy investor may recognize the true value of a stock through intense research and make profits by either go long if the stock is undervalued or go short if the stock is overvalued.

Fundamental analysis encompasses, but not limited to the following aspects of a business:

P/E Ratio

P/E ratio or in short PE is perhaps the most popular number of any business and refers to the price of the stock in relation with its earnings per share. PE is calculated by dividing the stock price to the company’s annual EPS:

P/E = Stock Price/ annual EPS

For example, a stock with a share price of $20 and an annual EPS of $2 will have a P/E of 20/2 = 10. The rational of the calculation is to find out the rate of return of an investment when buying the stock. In this case, an investment of $20 will yield a rate of return of 2/20 or 10% for the investor. This return will be factored into the stock price or distributed to the investor in form of dividends. If the company decides to reinvest its $2 of earnings and not to distribute it to shareholders, logically the stock price will jump to $22 a share. In the latter case, because the $2 has been distributed, the stock price may remains the same.

There are cases that the company's guidance is so positive for quarters to come that investors anticipate the good news and bid up the stock price to unreasonable prices, thus pumping the actual PE higher. This is true for high growth, mostly technological companies.

In case that the company doesn't record any earnings yet, for example a startup company, fundamentalists use other measures, such as revenue growth to assess a fair price.

Therefore, when a company reports an annual EPS of $2 and the average PE of its industry is about 10, investors may expect that the fair price of the stock should be $20, provided that all other factors remain the same. Any deviation from $20 may constitute an opportunity for the investors to make profits by buying or selling the stock in the long run.

However, many limitations exist when using P/E ratio to predict a stock price, such as:

- Nobody knows when the market will adjust the “correct” price of a stock. It could be weeks, months, or years.

- Although the average PE of an industry may reveal the general consensus of investors toward such industry, nothing can justify a specific stock should have the same P/E as its competitors.

- Common sense dictates that the higher the P/E, the more the stock is overpriced and a low P/E should indicate that the stock is rather “cheap.” In reality, growth companies have commonly high P/E because the market is willing to pay more for future earnings of growth companies. On the opposite side, a low P/E may be a sign that the company is in trouble and investors are fleeing its stock and dropping its price.

- P/E ratio is a lagging indicator of the company performance and a number from the past. Although forward P/E may be forecasted by estimated earnings but the number is merely a calculated speculation and never a sure thing.

Earnings per Share (EPS)

The whole point of doing business is to make money, thus, earnings is of crucial importance for any company. A startup company may temporarily lose money because of investment costs but eventually, all investment efforts should generate profits which can be distributed to shareholders or retained for future projects and expansion.

Looking at the absolute number of net earnings only does not reveal much about the capability of a company to make money because of the size of existing shareholders or the number of outstanding shares. Therefore, a common way to compare earnings of two companies is to look at Earnings Per Share (EPS), calculated by dividing net earnings to outstanding shares:

EPS = Net Earnings / Outstanding Shares

For example, two companies A and B both earn $1 million annually, but company A has 1 million shares outstanding, while company B has only 500,000 shares outstanding. So company A will have an EPS of $1 million / 1 million shares = $1. On the other hand, company B will have an EPS of $1 million / 500,000 shares = $2. Comparing the two companies, provided that all other factors are equal, we can deduct that company B should deserve a higher stock price than company A.

However, EPS alone does not tell the whole tale because reported EPS is a number from the past and does not guaranty future performance of the company. Analysts use commonly three kinds of EPS which are (1) Trailing EPS, last year’s numbers and the actual EPS, (2) Current EPS, this year’s reported numbers and the remaining quarter(s) EPS, and (3) Forward EPS, which are estimates of next year EPS.

Revenue

Revenue is defined as the total amount of money that a company receives from its normal business activities during a specific period, including discounts and refunds for returned merchandise. Commonly called as “gross income,” or “Gross operating income” revenue is of paramount importance for a company because profits can be made only when revenue surpasses the break even point of goods and services sold.

Another way to look at revenue is to observe revenue growth. A high revenue growth is an indicator that the company is gaining market share in its industry or entering a new niche market. Startup and high technology companies are among those companies while traditional and mature companies have consistent but low revenue growth.

Revenue may also come from sources other than normal business activities, for example from sales of assets, interest income, or depreciation amortization. In this case, revenue is categorized as other income.

Revenue reporting is based on particular standard accounting practices or rules established by a government or government agency. The most used method is called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Many countries are starting to use the International Reporting Standards (IFRS), established in 2001and maintained by the International Accounting Standards Committee in order to have the same framework of financial reporting for international trade.

Profit Margin

Profit margin is the ratio of profitability of a business, calculated by dividing net income to revenues, or net profits by sales. The ratio is useful when comparing companies in the same industry.

To come up with the final profit margin number, accounting methods measure initially the gross margin which is the percentage of revenue minus the cost of goods sold, divided by revenue. Then, the operating margin after deducting administrative and operating costs on top of the costs of goods sold, expressed by dividing operating income to total revenue.

Debts

Debts are considered liabilities of a business and always carry interest expenses which may be a burden for the business. However, debts are also a means of financial leverage and help the business to expand successfully its profitable operations. A company with no debts and plenty of cash in hand may be a sign that its market is saturated and the company can hardly grow anymore. On the other hand, high levels of debts may drain the company’s resources and leave little profits for shareholders.

When analyzing the fundamentals of a company, an investor should compare the debt/equity ratio of the company with its peers in the same industry. The financial sector is known to have the highest debt/equity ratio.

Current Ratio

Current Ratio is one of the most important aspects of fundamental analysis that an investor should know about a company. Current ratio reveals the ability of the company to payback its short-term liabilities (debts, payables) with its short-term assets (cash, receivables, inventory). In many cases, although a company equity is strongly positive but because a lack of short-term operating capital, the company may undergo imminent financial crisis. The current ratio is formulated as:

Current ratio = Currents Assets / Current Liabilities

A more stringent ratio commonly used by analysts is to eliminate inventory, which may be hard to convert to cash, from current assets. The ratio is called acid-test ratio. Firms with ratios of less than 1 should be looked with extreme caution because of the inability of such businesses to meet their current liabilities.

Fundamental analysis

In general, there are two main concepts or "schools" of investing: fundamental analysis and technical analysis. The two approaches are very much different from each other that fervent adherents in both schools simply refuse to admit the validity of the opposing school.

Fundamentalists believe that the market is so efficient that everything, such as news, anticipations, events at a certain point of time has been factored into the stock price. Another way to put it is that the stock market has the ability to discount all the influences on it. So no one can predict the future and the stock market follows a "random walk."

Therefore, the only way to invest soundly into the stock market is to do intensive research topside down from macroeconomics to microeconomics, then focusing on the company. Fundamentalists gather the most information they can about the company, compare them to other companies in the same industry and predict a future "reasonable" target stock price for the company, usually a year ahead. After research, analysts of the fundamental school may issue a recommendation that can be a strong buy, a buy, hold, sell or strong sell for the company.

Technical analysts on the other hand do not care about economics whatsoever. They agree too that the market is efficient and discounts all influences but by the time the investor can figure the reasons why, it is already too late and the market has passed him by.

Furthermore, trying to forecast a stock price by analyzing all the influences is too much work and futile. There are so many economical factors that could influence a stock and no one can properly identify them all. Also, technical analysts, also called chartists because their main tool is only a chart, believe that prices move in trends and history always repeats by itself. Therefore, if an investor can figure out the same patterns that are repeating, he can anticipate the move and get in or out at the right time. This can be called "timing the market."

Although pretty much counter-intuitive because who in their right minds want to invest into a company which they know nothing about it, the technical analysis approach has an advantage of self-fulfilling prophecy. Too many investors believe in it and therefore, they sell or buy in mass when they see signals on their charts.

Obviously, a combined approach of fundamental and technical analysis makes sense greatly. The common way is to use fundamental analysis to select a stock and then use charts (or technical analysis) to pick the right time to get in or out the market.

On this chapter we will deal with some of the most basic concepts of fundamental analysis.

Fundamental analysis refers to the research of company financial statements, its management and competitive advantages, and its environmental analysis. When applying to stocks, fundamental analysis aims to answer the vital question of “how to pick a winner.” Fundamental analysis is based on the concept that the market may misprice temporarily a stock and in the long run the correct price will eventually be reached. A savvy investor may recognize the true value of a stock through intense research and make profits by either go long if the stock is undervalued or go short if the stock is overvalued.

Fundamental analysis encompasses, but not limited to the following aspects of a business:

P/E Ratio

P/E ratio or in short PE is perhaps the most popular number of any business and refers to the price of the stock in relation with its earnings per share. PE is calculated by dividing the stock price to the company’s annual EPS:

P/E = Stock Price/ annual EPS

For example, a stock with a share price of $20 and an annual EPS of $2 will have a P/E of 20/2 = 10. The rational of the calculation is to find out the rate of return of an investment when buying the stock. In this case, an investment of $20 will yield a rate of return of 2/20 or 10% for the investor. This return will be factored into the stock price or distributed to the investor in form of dividends. If the company decides to reinvest its $2 of earnings and not to distribute it to shareholders, logically the stock price will jump to $22 a share. In the latter case, because the $2 has been distributed, the stock price may remains the same.

There are cases that the company's guidance is so positive for quarters to come that investors anticipate the good news and bid up the stock price to unreasonable prices, thus pumping the actual PE higher. This is true for high growth, mostly technological companies.

In case that the company doesn't record any earnings yet, for example a startup company, fundamentalists use other measures, such as revenue growth to assess a fair price.

Therefore, when a company reports an annual EPS of $2 and the average PE of its industry is about 10, investors may expect that the fair price of the stock should be $20, provided that all other factors remain the same. Any deviation from $20 may constitute an opportunity for the investors to make profits by buying or selling the stock in the long run.

However, many limitations exist when using P/E ratio to predict a stock price, such as:

- Nobody knows when the market will adjust the “correct” price of a stock. It could be weeks, months, or years.

- Although the average PE of an industry may reveal the general consensus of investors toward such industry, nothing can justify a specific stock should have the same P/E as its competitors.

- Common sense dictates that the higher the P/E, the more the stock is overpriced and a low P/E should indicate that the stock is rather “cheap.” In reality, growth companies have commonly high P/E because the market is willing to pay more for future earnings of growth companies. On the opposite side, a low P/E may be a sign that the company is in trouble and investors are fleeing its stock and dropping its price.

- P/E ratio is a lagging indicator of the company performance and a number from the past. Although forward P/E may be forecasted by estimated earnings but the number is merely a calculated speculation and never a sure thing.

Earnings per Share (EPS)

The whole point of doing business is to make money, thus, earnings is of crucial importance for any company. A startup company may temporarily lose money because of investment costs but eventually, all investment efforts should generate profits which can be distributed to shareholders or retained for future projects and expansion.

Looking at the absolute number of net earnings only does not reveal much about the capability of a company to make money because of the size of existing shareholders or the number of outstanding shares. Therefore, a common way to compare earnings of two companies is to look at Earnings Per Share (EPS), calculated by dividing net earnings to outstanding shares:

EPS = Net Earnings / Outstanding Shares

For example, two companies A and B both earn $1 million annually, but company A has 1 million shares outstanding, while company B has only 500,000 shares outstanding. So company A will have an EPS of $1 million / 1 million shares = $1. On the other hand, company B will have an EPS of $1 million / 500,000 shares = $2. Comparing the two companies, provided that all other factors are equal, we can deduct that company B should deserve a higher stock price than company A.

However, EPS alone does not tell the whole tale because reported EPS is a number from the past and does not guaranty future performance of the company. Analysts use commonly three kinds of EPS which are (1) Trailing EPS, last year’s numbers and the actual EPS, (2) Current EPS, this year’s reported numbers and the remaining quarter(s) EPS, and (3) Forward EPS, which are estimates of next year EPS.

Revenue

Revenue is defined as the total amount of money that a company receives from its normal business activities during a specific period, including discounts and refunds for returned merchandise. Commonly called as “gross income,” or “Gross operating income” revenue is of paramount importance for a company because profits can be made only when revenue surpasses the break even point of goods and services sold.

Another way to look at revenue is to observe revenue growth. A high revenue growth is an indicator that the company is gaining market share in its industry or entering a new niche market. Startup and high technology companies are among those companies while traditional and mature companies have consistent but low revenue growth.

Revenue may also come from sources other than normal business activities, for example from sales of assets, interest income, or depreciation amortization. In this case, revenue is categorized as other income.

Revenue reporting is based on particular standard accounting practices or rules established by a government or government agency. The most used method is called Generally Accepted Accounting Principles (GAAP). Many countries are starting to use the International Reporting Standards (IFRS), established in 2001and maintained by the International Accounting Standards Committee in order to have the same framework of financial reporting for international trade.

Profit Margin

Profit margin is the ratio of profitability of a business, calculated by dividing net income to revenues, or net profits by sales. The ratio is useful when comparing companies in the same industry.

To come up with the final profit margin number, accounting methods measure initially the gross margin which is the percentage of revenue minus the cost of goods sold, divided by revenue. Then, the operating margin after deducting administrative and operating costs on top of the costs of goods sold, expressed by dividing operating income to total revenue.

Debts

Debts are considered liabilities of a business and always carry interest expenses which may be a burden for the business. However, debts are also a means of financial leverage and help the business to expand successfully its profitable operations. A company with no debts and plenty of cash in hand may be a sign that its market is saturated and the company can hardly grow anymore. On the other hand, high levels of debts may drain the company’s resources and leave little profits for shareholders.

When analyzing the fundamentals of a company, an investor should compare the debt/equity ratio of the company with its peers in the same industry. The financial sector is known to have the highest debt/equity ratio.

Current Ratio

Current Ratio is one of the most important aspects of fundamental analysis that an investor should know about a company. Current ratio reveals the ability of the company to payback its short-term liabilities (debts, payables) with its short-term assets (cash, receivables, inventory). In many cases, although a company equity is strongly positive but because a lack of short-term operating capital, the company may undergo imminent financial crisis. The current ratio is formulated as:

Current ratio = Currents Assets / Current Liabilities

A more stringent ratio commonly used by analysts is to eliminate inventory, which may be hard to convert to cash, from current assets. The ratio is called acid-test ratio. Firms with ratios of less than 1 should be looked with extreme caution because of the inability of such businesses to meet their current liabilities.

Loading