Tìm Kiếm Bài Đã Đăng

Diễn Đàn Cựu Sinh Viên Quân Y

© 2015

© 2015

Preface to the Third Edition

Đức, or, Triumph of the Absurd

Forty years ago, absurdity triumphed in South Vietnam. On April 30, 1975, the wrong side conquered this tortured country. The Communists did not achieve their victory because they owned the moral high ground, as their adulators in the Western world would have us believe. They crushed South Vietnam with torture, mass murder and other horrendous acts of terror committed with cold strategic intent in violation of international law. I lived in Paris when their tanks crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon. As I watched this on television, I wondered: How did they manage to gain the upper hand after their clear military defeat I had witnessed as a combat correspondent during the Têt Offensive in Huế in 1968?

The answer can be found in the sinister prediction by Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, the North Vietnamese defense minister: “The enemy, meaning, the West… does not possess the psychological and political means to fight a long-drawn-out war.” In his commentary on the fall of Saigon, Adelbert Weinstein, the brilliant military specialist of Germany’s renowned Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung summed up the reason for the victory of this totalitarian power in one short, elegiac sentence: “America could not wait.”

Giap’s prophetic words and the adjective, absurd, will reappear time and again in several chapters of this book. They are meant to be a recurrent theme intended to remind my readers why I wrote this memoir of my five years in Vietnam four decades later.

I would like this leitmotif to shine through the potpourri of mirthful or sad, erotic as well as lethal episodes in my narrative. Equally important is a second theme underlying these reminiscences: my declaration of love for the wounded, betrayed and abandoned people of South Vietnam whom the authors of many other books about this war have arrogantly and absurdly assigned a subordinate place.

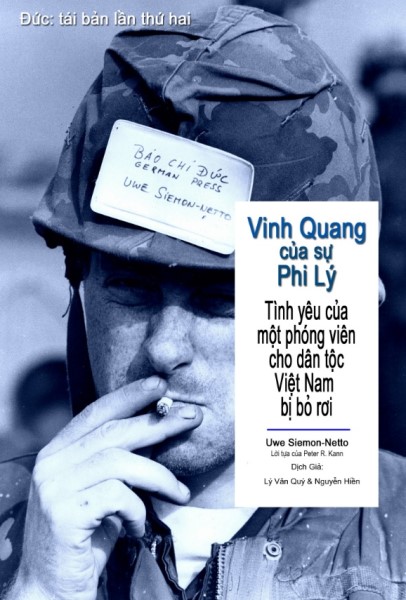

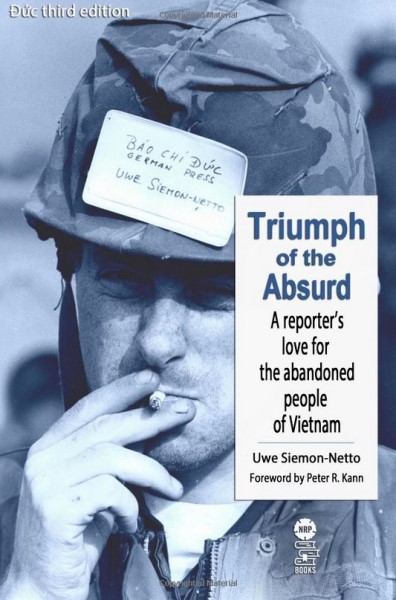

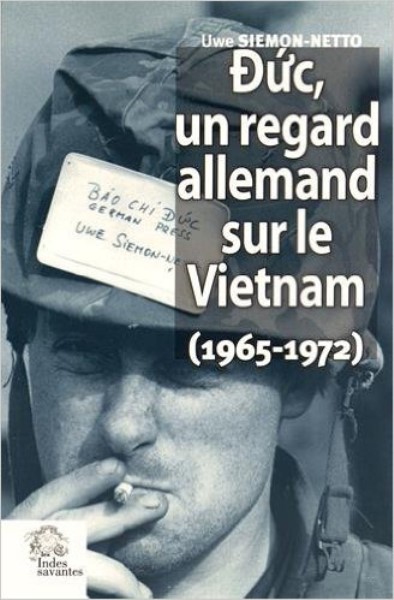

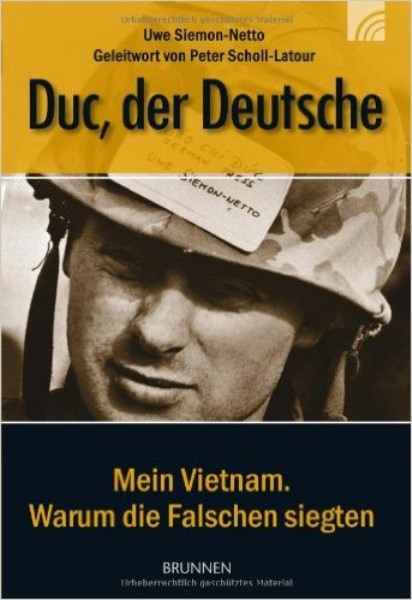

This is why, beginning with the second edition, I have renamed this memoir Triumph of the Absurd, replacing the initial title, Đức. But I would like to make it clear that this original title is still very much on my mind, for three reasons: 1. Đức is the Vietnamese term for German, and these are after all the reminiscences of a German war correspondent. 2. Đức was the nickname my Vietnamese friends gave me when I lived among them. 3. Đức was the name of two of my protagonists, one a buffalo boy in central Vietnam, and the other a feisty and amusing urchin I befriended in Saigon.

That latter Đức, whom I will now introduce in this preface, was the spindly leader of a gang of homeless kids roaming the sidewalks of “my” block of Tu Do Street. We met in 1965 when Tu Do, the former Rue Catinat, still displayed traces of its former French colonial charm; it was still shaded by bushy and bright green tamarind trees, which would later fall victim to the exhaust fumes of tens of thousands of mopeds with two-stroke engines and prehistoric cars such as my grey 1938 Citroen 15 CV Traction Avant, the “gangster car” of French film classics. This car was nearly my age, a metric ton of elegance on wheels -- and very thirsty; eight miles were all she gave me for a gallon of gasoline, provided her fuel tank had not sprung a leak, which my mechanic managed to seal swiftly every time with moist Wrigley gum harvested from inside his cheeks.

As you will presently see, my friendship with Đức and my love for this car were entwined. In truth, it wasn’t really my car. I had leased it from Josyane, a comely French Hertz concessionaire who, as I later found out, was also the agent of assorted Western European intelligence agencies, including the BND, Germany’s equivalent of the CIA. I had often wondered why Josyane rummaged furtively through the manuscripts on my desk when she joined my friends and me for “sundowners” in Suite 214 of the Continental Palace. I fantasized that she was attracted by my youthful and slender Teutonic looks and my stiff dry martinis. She never let on that she read German; why would she want to stare at my texts if they were incomprehensible to her? Well, now I know: She was a spook, according to the Dutch station chief, possibly one of her lovers. But that was alright! I loved her car and she loved my martinis, which she handed around with amazing grace, and she was welcome to my stories anytime; after all, they were written for the public at large.

But my mind is wandering. Let us return to Đức. He was a droll twelve-year old with a mischievous grin reminding me of myself when I was his age, a rascal in a large wartime city. True, I wasn’t homeless like Đức, although the British Lancaster bombers and the American Flying Fortresses pummeling Leipzig night and day during the final years of World War II tried their best to render me that way.

Like Đức, I was an impish big-town boy successfully bossing other kids on my block around. Đức was different. He was an urchin with a high sense of responsibility. He protectively watched over a gang of much younger orphans living on Tu Do between Le Loi Boulevard and Le Than Ton Street, reporting to a middle-aged Mamasan headquartered on the sidewalk outside La Pagode, a café famed for its French pastries, and the renowned rendezvous point of pre-Communist Saigon’s jeunesse dorée. Mamasan was the motherly press tycoon of that part of the capital. She squatted there outside La Pagode surrounded by stacks of newspapers: papers in Vietnamese and English, French and Chinese - the Vietnamese were avid readers. She handed them out to Đức and his wards and several other bands of children assigned to neighboring blocks.

From what I could observe, Đức was Mamasan’s most important lieutenant, the head paperboy at the busiest end of his block. His turf was the sidewalk between Givral, a restaurant renowned for its Chinese noodle soup as well as the most authentic French onion soup in all of Southeast Asia, and the entrance to the shopping passage in the Eden Building, which housed the consular section of the West German embassy at that time and the offices of the Associated Press. I fancy that I was one of Đức’s favorite clients because I bought the Saigon Daily News and the Vietnam Guardian from him every day, and the Saigon Post and the Journal d’Extrême Orient. Sometimes I allowed him to cajole me into paying for a couple of Vietnamese-language papers; not that I could read them, but I was intrigued by their frequent empty spaces, the handiwork of government censors.

One late afternoon at the onset of the monsoon season, Đức and I became business partners. The massive clouds in the tropical sky were about to burst. Sheets of water threatened to descend on me with the force of a guillotine blade transforming Saigon’s principal thoroughfare into a gushing stream. I hastily squeezed my Traction into a tight parking space outside Givral’s, a muscle-building exercise given that this front wheel-driven machine lacked power steering and was propelled by a heavy six-cylinder motor made of cast iron. Exhausted, I switched off the engine by which time I was lusting for a bottle of Bière Larue on the Continental Palace’s open-air terrace when Đức stopped me.

The old Traction’s front doors opened forward, thus in the opposite direction of the doors of all modern cars. As I tried to dash out, Đức stood in my way pointing at the windscreen sticker I had been issued that morning by my embassy. It bore the German national colors, black, red and gold, and identified me as “Báo Chí Đức,” a German journalist. This was meant to protect me in case I ran into a Viet Cong roadblock on my occasional weekend jaunts to Cap Saint-Jacques, now called Vũng Tàu, a seaside resort once known as the St. Tropez of the Orient. It actually did shield me in those days. Whenever I ran into a patrol of black-clad Communist militiamen, they would charge me a toll and let me go, but not before issuing me a stamped receipt.

“You Đức!” he shouted delightedly. “My name Đức. We both Đức. We like brothers!” We shook hands. Now I had a younger brother in Saigon; later I learned that his remark meant even more: it was wordplay. Đức is also the Vietnamese word for virtuous.

Having established our bond, he wouldn’t let me go, though. “Okay, okay,” he said. “Rain coming, Đức, rain numbah ten.” I knew Saigon street jargon well enough to realize that my new brother wasn’t talking of the tenth rainfall. No, “numbah ten” meant the worst, the pits, something definitely to avoid.

“Okay, okay,” Đức continued. “You Đức, you numbah one (the best). You and I do business, okay?”

Then he outlined our deal: I was to allow him and his wards to seek shelter in my Traction. It would become their bedroom, which they promised to keep immaculately clean. If I wanted to leave any valuables in the car, they would be safe. Its lock no longer worked; this much Đức had already ascertained.

“Okay, okay, Đức?” he pleaded impatiently.

I nodded. He whistled, and at once nine toddlers rushed out of several doorways and piled into my Traction. Three curled up on the back seats, two on the jump seats, one each in the legroom separating them, one girl took the right front seat, another squatted on the generous floor space under her feet, and Đức naturally took his place behind the steering wheel.

“Bonne nuit, Đức, you numbah one!” he said, slamming the door and winding up the window. At this moment a torrent of rain poured down on the Traction and on me. The kids were safe. I was drenched to the bones within seconds. I ran into the Continental, needing more than a Larue.

First I had a shower in my room, then a whisky on the covered terrace. As night fell I kept staring across Tu Do Street at my large Citroen with steamed up windows outside Givral’s. This sight pleased me. These children were warm and dry. In all my years in Vietnam I rarely felt as happy as on that evening, an uncommon sensation in a reporter’s life.

I am honoring Đức in this book too because in my mind he personified many qualities that formed my affection and admiration for the people of South Vietnam, and my compassion for them after their abandonment by their protectors and their betrayal by some, though not all, members of my profession. Like Đức, they are feisty and resilient; they don’t whine, but pull themselves up by their bootstraps, and they care for each other. When they are down, they rise again and accomplish astonishing things.

I am in awe of the achievements of the hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese living and working close to my home in southern California. I am full of admiration for those former boat people and survivors of Communist reeducation camps, those former warriors suffering in silence from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and other severe ailments caused by torture and head injuries received in combat.

I hope that Đức’s adolescence and adulthood turned out to be a success story as well, but I don’t know. We lost contact 18 months after our first encounter. Was he drafted into the South Vietnamese army and eventually killed in combat? Did he join the Vietcong and perhaps die in their service? Was he among the thousands of civilians butchered by the Vietcong during the Têt Offensive of 1968? Or did this crafty kid manage to flee his homeland after the Communist victory of 1975? Perhaps he is alive at the time of this writing and is a successful 58-year old businessman or professional in Westminster, California, just up the road from me; perhaps he is reading this book.

I thought of Đức when two wonderful Vietnamese friends, Quy Van Ly and his wife QuynhChau, better known as Jo, invited me to address a convention of former military medical officers of the South Vietnamese Army. They had been urging me for some time to write my wartime reminiscences. “Do it for us,” they said, “do it for our children’s generation. They want to know what it was like. You have special credibility because as a German you had no dog in this fight.” Then, after listening to my anecdotes (such as the one about my encounter with Đức) several of those retired physicians, dentists and pharmacists in my audience said the same thing, and some bounced my speech around the Internet.

I do not presume to rewrite the history of the Vietnam War or even give a comprehensive account of the nearly five years I spent in Indochina as a correspondent first of the Axel Springer group of German newspapers and subsequently as a visiting reporter of Stern, an influential Hamburg-based magazine. I beg my readers not to expect me to take sides in the domestic squabbles between South Vietnamese factions, quarrels that are being perpetuated in the huge communities of Vietnamese exiles today. When I mention former Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, for example, this does not mean that I favor him over former President Nguyen van Thieu, or vice versa; I am just here to tell stories, including some about Ky and some about Thieu, without wishing to pass judgment on either. Theirs was an unenviable lot, and they deserve my respect for having taken up an appalling burden.

As I stated in the first paragraph of this preface, I did not welcome the victory of the Communists in 1975. They deserved this triumph as little as the Taliban in Afghanistan will deserve the triumph, which I fear will be theirs once NATO forces have left their country. It is also with this latter sinister prospect in mind that I have written this book.

In Vietnam, I have been a witness to heinous atrocities the Communists committed as a matter of policy, a witness to mass murder and carnage beside which transgressions against the rules of war perpetrated on the American and South Vietnamese side - clearly not as a matter of policy or strategy - appear pale in comparison. I know that many in the American and international mass media and academe have unjustly, gratuitously and arrogantly maligned the South Vietnamese and are still doing so. I was disgusted by the way returning GIs were treated by their fellow countrymen and am shocked by the fact that the continued suffering of South Vietnamese veterans is not deemed worthy of consideration by U.S. journalists.

This book is a collection of personal sketches recounting what I saw, observed, lived through and reported in my Vietnam years, and about the people I met. It is a series of alternating narratives about experiences ranging from the horrific to the absurd, about pursuits ranging from the glamorous to the frivolous, and about life ranging from despair to hope. All the persons mentioned here are authentic, though in some cases I changed their names to protect them or their next of kin.

Vietnam has had a significant impact on my spiritual life as well. But this process, which took decades, will not be a major feature in the present volume because I intend to elaborate on it in a different kind of memoir later. But I will mention it briefly in this preface: Gradually, my war experiences in Vietnam have led me back to the Christian faith to which my maternal grandmother, Clara Netto, introduced me in our air raid shelter in Leipzig as blockbuster bombs detonated all around us. It was in those fearful moments that she taught me to place my trust in God: She held me tightly and sang to me softly Lutheran hymns, especially one that was to remain in my ears for the rest of my life:

Abide, O dearest Jesus,

Among us with Thy grace,

That Satan may not harm us,

Nor we to sin give place.

To say that I was filled with Christian fervor in the nineteen-sixties would be mendacious. Like my contemporaries, I indulged in a lifestyle filled with worldly pleasures of which chain-smoking was the least iniquitous, particularly as nicotine has a seemingly numbing effect in combat situations, as almost all frontline soldiers and war reporters will affirm. The photograph on the cover of this book shows me sucking grimly on a cigarette during a lull in the battle of Hué in 1968. We chose this picture because it is authentic and realistic. This is how people look after they have seen others die all around them for many days and nights; this is how I looked as a young man in an unforgettably terrifying situation, which determined the course of the rest of my life.

Though a hedonist then, I was never an atheist. I spoke the Lord’s Prayer frequently, subsequently humming in my head the Lutheran offertory versicle based on the 51st Palm: “Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a right spirit within me. Cast me not away from Thy presence, and take not Thy Holy spirit from me.” When I was in heavy combat, holding the hand of a dying soldier, I chanted to myself the Kyrie eleison: Lord, have mercy!

Today I am grateful for having been brought up with the rich liturgy of the Lutheran Church in Saxony. Its words, all taken from Scripture, have become deeply ingrained in my memory. But following Saint Augustine’s example, I had relegated God to the waiting room of my biography. Too enticing were those dark-haired beauties in whose arms we reporters found solace from he war, too wonderful were the food and wine in Saigon’s French restaurants, too jolly was the fellowship of my witty British colleagues.

Then in 1973, the year the Americans turned their backs on South Vietnam, I was shocked to hear myself profess my faith in Christ in the absurdly godless environment of a German newsroom where I was the managing editor. The circumstances of this sudden commitment during a fierce slugfest with extreme leftwing members of my staff will make a hilarious chapter of a future book. Suffice it to say that this was a turning point in my life, which after many temptations and much inner strife led me to enroll in the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago thirteen years later.

Slowly, almost homeopathically, Vietnam had changed me. At first I thought I was called to the ordained ministry, until my astute wife, Gillian, set me straight, convincing me that with the acerbic manner, nurtured as a battle-scarred reporter would split any congregation within 24 hours. “Your place in church is neither at the altar nor in the pulpit but in one of the back pews from which you can seek refuge at the nearest pub when you hear a bad sermon,” she said. And she was right.

Before opting for the strictly academic route to theology, though, I enrolled in a Clinical Pastoral Education program that is a prerequisite for ordination in the United States. I took this course at the Veterans Hospital in St. Cloud, Minnesota, where I asked my superiors to assign me to Vietnam veterans. I immediately encountered hosts of broken men describing to me the bone-headed cruelty with which their fellow Americans, especially young women, disowned them. I discovered that almost all of them were convinced that God had long condemned them to hell for all eternity. God, they said, had deserted them in Vietnam.

This gave me an excellent starting point for providing them with pastoral care, especially as I had concentrated heavily on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s take on the Lutheran Theology of the Cross in my studies. Together with VA psychologist James Tuorila I formed therapy groups of 30 men each, ranging from former private to lieutenant colonel. I made them read Bonhoeffer’s Letters and Papers from Prison. What fascinated them most about this stirring book was Bonhoeffer’s emphasis on Jesus’ words to his disciples in Gethsemane, “Could you not stay awake with me one hour?” (Matthew 26:40). “This is the reversal of everything a religious person expected from God”, Bonhoeffer wrote. “The human being is called upon to share in God’s suffering in a godless world.”

This was the first time these former warriors were told a basic Christian verity: The Christian is called to suffer with God in this world as an act of discipleship. Their suffering in Vietnam and after, in their return home was the cross God had placed on their backs. But this means that God himself also suffers in the world from the godlessness these men of war experience daily. That being so, God is clearly not the deserter they thought he was. Quite to the contrary, he is a fellow sufferer, a comrade.

I taped these discussions, edited and commented them, and thus turned them into my M.A. thesis, which I presented to the Lutheran School of Theology. In 1990, this thesis was published as a book, which is still in print and used as a textbook for providing pastoral care to veterans.

Then I found an entirely different occasion for dealing with the topic of Vietnam. After earning my M.A. in Chicago, I transferred to Boston University to study for my interdisciplinary doctorate in theology and sociology of religion. This triggered my interest in the sociological phenomenon of thinking in clichés.

Used as a metaphor for a particular way of thinking, clichés distinguish themselves by “their capacity to bypass reflection and thus unconsciously to work on the mind, while excluding potential relativizations,” according to the Dutch sociologist Anton Zijderveld (Zijderveld, Anton: On Clichés, London 1979). “Having been fully socialized in a particular society,” Zijderveld writes, “the clichés of this society will lie in store in man’s consciousness, ever ready to be triggered and used.”

Clichés, or stereotypes, thus become “containers of old experiences” that have “grown stale and common through repetitive overuse,” Zijderveld continues. They are exchanged “like the many coins of our inflated economic system.” A cliché should be seen “as a specimen of human expression which has lost much of its original ingenuity and semantic power, but gained in social functionality.”

Zijderveld saw a strong affinity between clichés and modernity. In my doctoral dissertation I took this though a step further: If Zijderveld is right then stereotypical thinking is a twin of the Zeitgeist, which also does not allow for any relativizations. The Zeitgeist shares a property Zijderveld attributes to clichés: “They become tyrannical in that stereotypes are hard to avoid in a fully modernized society; they are prone to become the molds of consciousness, while their functionality penetrates deeply into the fabric of socio-cultural and political life.”

To be sure, Vietnam was not the topic of my dissertation, with which I refuted the widely held stereotype that Martin Luther had paved the way for Adolf Hitler. I did this by pointing to large number of relativizing factors disproving this contemptible slander. In the present book, however, I am attempting something similar concerning Vietnam, though not in a scholarly manner but just by relating my personal experiences and observations.

Forty years after the communist conquest of Saigon, a stereotypical lump lies heavily on peoples collective consciousness: the absurd cliché that this victory, which was accomplished by means of torture and mass murder, was actually an act of liberation and thus a good thing. In its tyrannical way, as Zijderveld would say, this cliché allowed for no relativizing factors of the kind I describe graphically in order to counter a historical lie.

To remind my readers and myself that this is ultimately a book about a tragic war that ended in defeat for the victims of aggression, I will insert a brief reflection underscoring this fact every few chapters, beginning with a description of a mass murder the Communists committed during the 1968 Têt Offensive.

I owe gratitude to many people, but especially to my faithful friends Quy and Jo who steadfastly stood behind me as I wrote this book giving me every conceivable support while I labored over the manuscript. Every time I had finished a chapter, Quy translated it immediately into elegant Vietnamese with the help of his friend Nguyen Hien. He did the layout, designed the cover and gave me sound advice on cultural and historical questions. I am proud to have become part of Quy’s and Jo’s very traditional Vietnamese family in Orange County. I thank Quy’s brother-in- law, Di Ton That, and his wife, Tran, who were the first to contact me when I moved to southern California, and who introduced me to the huge and thriving Vietnamese community in Orange County.

I am grateful to the absent Đức, and to the countless other Vietnamese, American, French, British and German friends I made in Vietnam. I also wish to thank the Vietnam veterans whom I served as a chaplain intern at the VA Medical Center in St. Cloud, Minnesota, and the psychologists and ministers with whom I worked in order to provide those former soldiers with pastoral care. I am very thankful to my friend Perry Kretz for allowing me to publish some of his magnificent photographs from our reporting trip to Vietnam in 1972 in this volume.

I thank my friend and editor Peggy Strong and, most importantly, my wife Gillian who in our 50 years of marriage has stood by me and endured our long periods of separation caused by my assignment to an enchanting war-torn country I have come to love.

Uwe Siemon-Netto LagunaWoods, Calififornia

January 2015

Đức, or, Triumph of the Absurd

Forty years ago, absurdity triumphed in South Vietnam. On April 30, 1975, the wrong side conquered this tortured country. The Communists did not achieve their victory because they owned the moral high ground, as their adulators in the Western world would have us believe. They crushed South Vietnam with torture, mass murder and other horrendous acts of terror committed with cold strategic intent in violation of international law. I lived in Paris when their tanks crashed through the gates of the Presidential Palace in Saigon. As I watched this on television, I wondered: How did they manage to gain the upper hand after their clear military defeat I had witnessed as a combat correspondent during the Têt Offensive in Huế in 1968?

The answer can be found in the sinister prediction by Gen. Vo Nguyen Giap, the North Vietnamese defense minister: “The enemy, meaning, the West… does not possess the psychological and political means to fight a long-drawn-out war.” In his commentary on the fall of Saigon, Adelbert Weinstein, the brilliant military specialist of Germany’s renowned Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung summed up the reason for the victory of this totalitarian power in one short, elegiac sentence: “America could not wait.”

Giap’s prophetic words and the adjective, absurd, will reappear time and again in several chapters of this book. They are meant to be a recurrent theme intended to remind my readers why I wrote this memoir of my five years in Vietnam four decades later.

I would like this leitmotif to shine through the potpourri of mirthful or sad, erotic as well as lethal episodes in my narrative. Equally important is a second theme underlying these reminiscences: my declaration of love for the wounded, betrayed and abandoned people of South Vietnam whom the authors of many other books about this war have arrogantly and absurdly assigned a subordinate place.

This is why, beginning with the second edition, I have renamed this memoir Triumph of the Absurd, replacing the initial title, Đức. But I would like to make it clear that this original title is still very much on my mind, for three reasons: 1. Đức is the Vietnamese term for German, and these are after all the reminiscences of a German war correspondent. 2. Đức was the nickname my Vietnamese friends gave me when I lived among them. 3. Đức was the name of two of my protagonists, one a buffalo boy in central Vietnam, and the other a feisty and amusing urchin I befriended in Saigon.

That latter Đức, whom I will now introduce in this preface, was the spindly leader of a gang of homeless kids roaming the sidewalks of “my” block of Tu Do Street. We met in 1965 when Tu Do, the former Rue Catinat, still displayed traces of its former French colonial charm; it was still shaded by bushy and bright green tamarind trees, which would later fall victim to the exhaust fumes of tens of thousands of mopeds with two-stroke engines and prehistoric cars such as my grey 1938 Citroen 15 CV Traction Avant, the “gangster car” of French film classics. This car was nearly my age, a metric ton of elegance on wheels -- and very thirsty; eight miles were all she gave me for a gallon of gasoline, provided her fuel tank had not sprung a leak, which my mechanic managed to seal swiftly every time with moist Wrigley gum harvested from inside his cheeks.

As you will presently see, my friendship with Đức and my love for this car were entwined. In truth, it wasn’t really my car. I had leased it from Josyane, a comely French Hertz concessionaire who, as I later found out, was also the agent of assorted Western European intelligence agencies, including the BND, Germany’s equivalent of the CIA. I had often wondered why Josyane rummaged furtively through the manuscripts on my desk when she joined my friends and me for “sundowners” in Suite 214 of the Continental Palace. I fantasized that she was attracted by my youthful and slender Teutonic looks and my stiff dry martinis. She never let on that she read German; why would she want to stare at my texts if they were incomprehensible to her? Well, now I know: She was a spook, according to the Dutch station chief, possibly one of her lovers. But that was alright! I loved her car and she loved my martinis, which she handed around with amazing grace, and she was welcome to my stories anytime; after all, they were written for the public at large.

But my mind is wandering. Let us return to Đức. He was a droll twelve-year old with a mischievous grin reminding me of myself when I was his age, a rascal in a large wartime city. True, I wasn’t homeless like Đức, although the British Lancaster bombers and the American Flying Fortresses pummeling Leipzig night and day during the final years of World War II tried their best to render me that way.

Like Đức, I was an impish big-town boy successfully bossing other kids on my block around. Đức was different. He was an urchin with a high sense of responsibility. He protectively watched over a gang of much younger orphans living on Tu Do between Le Loi Boulevard and Le Than Ton Street, reporting to a middle-aged Mamasan headquartered on the sidewalk outside La Pagode, a café famed for its French pastries, and the renowned rendezvous point of pre-Communist Saigon’s jeunesse dorée. Mamasan was the motherly press tycoon of that part of the capital. She squatted there outside La Pagode surrounded by stacks of newspapers: papers in Vietnamese and English, French and Chinese - the Vietnamese were avid readers. She handed them out to Đức and his wards and several other bands of children assigned to neighboring blocks.

From what I could observe, Đức was Mamasan’s most important lieutenant, the head paperboy at the busiest end of his block. His turf was the sidewalk between Givral, a restaurant renowned for its Chinese noodle soup as well as the most authentic French onion soup in all of Southeast Asia, and the entrance to the shopping passage in the Eden Building, which housed the consular section of the West German embassy at that time and the offices of the Associated Press. I fancy that I was one of Đức’s favorite clients because I bought the Saigon Daily News and the Vietnam Guardian from him every day, and the Saigon Post and the Journal d’Extrême Orient. Sometimes I allowed him to cajole me into paying for a couple of Vietnamese-language papers; not that I could read them, but I was intrigued by their frequent empty spaces, the handiwork of government censors.

One late afternoon at the onset of the monsoon season, Đức and I became business partners. The massive clouds in the tropical sky were about to burst. Sheets of water threatened to descend on me with the force of a guillotine blade transforming Saigon’s principal thoroughfare into a gushing stream. I hastily squeezed my Traction into a tight parking space outside Givral’s, a muscle-building exercise given that this front wheel-driven machine lacked power steering and was propelled by a heavy six-cylinder motor made of cast iron. Exhausted, I switched off the engine by which time I was lusting for a bottle of Bière Larue on the Continental Palace’s open-air terrace when Đức stopped me.

The old Traction’s front doors opened forward, thus in the opposite direction of the doors of all modern cars. As I tried to dash out, Đức stood in my way pointing at the windscreen sticker I had been issued that morning by my embassy. It bore the German national colors, black, red and gold, and identified me as “Báo Chí Đức,” a German journalist. This was meant to protect me in case I ran into a Viet Cong roadblock on my occasional weekend jaunts to Cap Saint-Jacques, now called Vũng Tàu, a seaside resort once known as the St. Tropez of the Orient. It actually did shield me in those days. Whenever I ran into a patrol of black-clad Communist militiamen, they would charge me a toll and let me go, but not before issuing me a stamped receipt.

“You Đức!” he shouted delightedly. “My name Đức. We both Đức. We like brothers!” We shook hands. Now I had a younger brother in Saigon; later I learned that his remark meant even more: it was wordplay. Đức is also the Vietnamese word for virtuous.

Having established our bond, he wouldn’t let me go, though. “Okay, okay,” he said. “Rain coming, Đức, rain numbah ten.” I knew Saigon street jargon well enough to realize that my new brother wasn’t talking of the tenth rainfall. No, “numbah ten” meant the worst, the pits, something definitely to avoid.

“Okay, okay,” Đức continued. “You Đức, you numbah one (the best). You and I do business, okay?”

Then he outlined our deal: I was to allow him and his wards to seek shelter in my Traction. It would become their bedroom, which they promised to keep immaculately clean. If I wanted to leave any valuables in the car, they would be safe. Its lock no longer worked; this much Đức had already ascertained.

“Okay, okay, Đức?” he pleaded impatiently.

I nodded. He whistled, and at once nine toddlers rushed out of several doorways and piled into my Traction. Three curled up on the back seats, two on the jump seats, one each in the legroom separating them, one girl took the right front seat, another squatted on the generous floor space under her feet, and Đức naturally took his place behind the steering wheel.

“Bonne nuit, Đức, you numbah one!” he said, slamming the door and winding up the window. At this moment a torrent of rain poured down on the Traction and on me. The kids were safe. I was drenched to the bones within seconds. I ran into the Continental, needing more than a Larue.

First I had a shower in my room, then a whisky on the covered terrace. As night fell I kept staring across Tu Do Street at my large Citroen with steamed up windows outside Givral’s. This sight pleased me. These children were warm and dry. In all my years in Vietnam I rarely felt as happy as on that evening, an uncommon sensation in a reporter’s life.

I am honoring Đức in this book too because in my mind he personified many qualities that formed my affection and admiration for the people of South Vietnam, and my compassion for them after their abandonment by their protectors and their betrayal by some, though not all, members of my profession. Like Đức, they are feisty and resilient; they don’t whine, but pull themselves up by their bootstraps, and they care for each other. When they are down, they rise again and accomplish astonishing things.

I am in awe of the achievements of the hundreds of thousands of South Vietnamese living and working close to my home in southern California. I am full of admiration for those former boat people and survivors of Communist reeducation camps, those former warriors suffering in silence from Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder and other severe ailments caused by torture and head injuries received in combat.

I hope that Đức’s adolescence and adulthood turned out to be a success story as well, but I don’t know. We lost contact 18 months after our first encounter. Was he drafted into the South Vietnamese army and eventually killed in combat? Did he join the Vietcong and perhaps die in their service? Was he among the thousands of civilians butchered by the Vietcong during the Têt Offensive of 1968? Or did this crafty kid manage to flee his homeland after the Communist victory of 1975? Perhaps he is alive at the time of this writing and is a successful 58-year old businessman or professional in Westminster, California, just up the road from me; perhaps he is reading this book.

I thought of Đức when two wonderful Vietnamese friends, Quy Van Ly and his wife QuynhChau, better known as Jo, invited me to address a convention of former military medical officers of the South Vietnamese Army. They had been urging me for some time to write my wartime reminiscences. “Do it for us,” they said, “do it for our children’s generation. They want to know what it was like. You have special credibility because as a German you had no dog in this fight.” Then, after listening to my anecdotes (such as the one about my encounter with Đức) several of those retired physicians, dentists and pharmacists in my audience said the same thing, and some bounced my speech around the Internet.

I do not presume to rewrite the history of the Vietnam War or even give a comprehensive account of the nearly five years I spent in Indochina as a correspondent first of the Axel Springer group of German newspapers and subsequently as a visiting reporter of Stern, an influential Hamburg-based magazine. I beg my readers not to expect me to take sides in the domestic squabbles between South Vietnamese factions, quarrels that are being perpetuated in the huge communities of Vietnamese exiles today. When I mention former Vice President Nguyen Cao Ky, for example, this does not mean that I favor him over former President Nguyen van Thieu, or vice versa; I am just here to tell stories, including some about Ky and some about Thieu, without wishing to pass judgment on either. Theirs was an unenviable lot, and they deserve my respect for having taken up an appalling burden.

As I stated in the first paragraph of this preface, I did not welcome the victory of the Communists in 1975. They deserved this triumph as little as the Taliban in Afghanistan will deserve the triumph, which I fear will be theirs once NATO forces have left their country. It is also with this latter sinister prospect in mind that I have written this book.

In Vietnam, I have been a witness to heinous atrocities the Communists committed as a matter of policy, a witness to mass murder and carnage beside which transgressions against the rules of war perpetrated on the American and South Vietnamese side - clearly not as a matter of policy or strategy - appear pale in comparison. I know that many in the American and international mass media and academe have unjustly, gratuitously and arrogantly maligned the South Vietnamese and are still doing so. I was disgusted by the way returning GIs were treated by their fellow countrymen and am shocked by the fact that the continued suffering of South Vietnamese veterans is not deemed worthy of consideration by U.S. journalists.

This book is a collection of personal sketches recounting what I saw, observed, lived through and reported in my Vietnam years, and about the people I met. It is a series of alternating narratives about experiences ranging from the horrific to the absurd, about pursuits ranging from the glamorous to the frivolous, and about life ranging from despair to hope. All the persons mentioned here are authentic, though in some cases I changed their names to protect them or their next of kin.

Vietnam has had a significant impact on my spiritual life as well. But this process, which took decades, will not be a major feature in the present volume because I intend to elaborate on it in a different kind of memoir later. But I will mention it briefly in this preface: Gradually, my war experiences in Vietnam have led me back to the Christian faith to which my maternal grandmother, Clara Netto, introduced me in our air raid shelter in Leipzig as blockbuster bombs detonated all around us. It was in those fearful moments that she taught me to place my trust in God: She held me tightly and sang to me softly Lutheran hymns, especially one that was to remain in my ears for the rest of my life:

Abide, O dearest Jesus,

Among us with Thy grace,

That Satan may not harm us,

Nor we to sin give place.

To say that I was filled with Christian fervor in the nineteen-sixties would be mendacious. Like my contemporaries, I indulged in a lifestyle filled with worldly pleasures of which chain-smoking was the least iniquitous, particularly as nicotine has a seemingly numbing effect in combat situations, as almost all frontline soldiers and war reporters will affirm. The photograph on the cover of this book shows me sucking grimly on a cigarette during a lull in the battle of Hué in 1968. We chose this picture because it is authentic and realistic. This is how people look after they have seen others die all around them for many days and nights; this is how I looked as a young man in an unforgettably terrifying situation, which determined the course of the rest of my life.

Though a hedonist then, I was never an atheist. I spoke the Lord’s Prayer frequently, subsequently humming in my head the Lutheran offertory versicle based on the 51st Palm: “Create in me a clean heart, O God, and renew a right spirit within me. Cast me not away from Thy presence, and take not Thy Holy spirit from me.” When I was in heavy combat, holding the hand of a dying soldier, I chanted to myself the Kyrie eleison: Lord, have mercy!

Today I am grateful for having been brought up with the rich liturgy of the Lutheran Church in Saxony. Its words, all taken from Scripture, have become deeply ingrained in my memory. But following Saint Augustine’s example, I had relegated God to the waiting room of my biography. Too enticing were those dark-haired beauties in whose arms we reporters found solace from he war, too wonderful were the food and wine in Saigon’s French restaurants, too jolly was the fellowship of my witty British colleagues.

Then in 1973, the year the Americans turned their backs on South Vietnam, I was shocked to hear myself profess my faith in Christ in the absurdly godless environment of a German newsroom where I was the managing editor. The circumstances of this sudden commitment during a fierce slugfest with extreme leftwing members of my staff will make a hilarious chapter of a future book. Suffice it to say that this was a turning point in my life, which after many temptations and much inner strife led me to enroll in the Lutheran School of Theology at Chicago thirteen years later.

Slowly, almost homeopathically, Vietnam had changed me. At first I thought I was called to the ordained ministry, until my astute wife, Gillian, set me straight, convincing me that with the acerbic manner, nurtured as a battle-scarred reporter would split any congregation within 24 hours. “Your place in church is neither at the altar nor in the pulpit but in one of the back pews from which you can seek refuge at the nearest pub when you hear a bad sermon,” she said. And she was right.

Before opting for the strictly academic route to theology, though, I enrolled in a Clinical Pastoral Education program that is a prerequisite for ordination in the United States. I took this course at the Veterans Hospital in St. Cloud, Minnesota, where I asked my superiors to assign me to Vietnam veterans. I immediately encountered hosts of broken men describing to me the bone-headed cruelty with which their fellow Americans, especially young women, disowned them. I discovered that almost all of them were convinced that God had long condemned them to hell for all eternity. God, they said, had deserted them in Vietnam.

This gave me an excellent starting point for providing them with pastoral care, especially as I had concentrated heavily on Dietrich Bonhoeffer’s take on the Lutheran Theology of the Cross in my studies. Together with VA psychologist James Tuorila I formed therapy groups of 30 men each, ranging from former private to lieutenant colonel. I made them read Bonhoeffer’s Letters and Papers from Prison. What fascinated them most about this stirring book was Bonhoeffer’s emphasis on Jesus’ words to his disciples in Gethsemane, “Could you not stay awake with me one hour?” (Matthew 26:40). “This is the reversal of everything a religious person expected from God”, Bonhoeffer wrote. “The human being is called upon to share in God’s suffering in a godless world.”

This was the first time these former warriors were told a basic Christian verity: The Christian is called to suffer with God in this world as an act of discipleship. Their suffering in Vietnam and after, in their return home was the cross God had placed on their backs. But this means that God himself also suffers in the world from the godlessness these men of war experience daily. That being so, God is clearly not the deserter they thought he was. Quite to the contrary, he is a fellow sufferer, a comrade.

I taped these discussions, edited and commented them, and thus turned them into my M.A. thesis, which I presented to the Lutheran School of Theology. In 1990, this thesis was published as a book, which is still in print and used as a textbook for providing pastoral care to veterans.

Then I found an entirely different occasion for dealing with the topic of Vietnam. After earning my M.A. in Chicago, I transferred to Boston University to study for my interdisciplinary doctorate in theology and sociology of religion. This triggered my interest in the sociological phenomenon of thinking in clichés.

Used as a metaphor for a particular way of thinking, clichés distinguish themselves by “their capacity to bypass reflection and thus unconsciously to work on the mind, while excluding potential relativizations,” according to the Dutch sociologist Anton Zijderveld (Zijderveld, Anton: On Clichés, London 1979). “Having been fully socialized in a particular society,” Zijderveld writes, “the clichés of this society will lie in store in man’s consciousness, ever ready to be triggered and used.”

Clichés, or stereotypes, thus become “containers of old experiences” that have “grown stale and common through repetitive overuse,” Zijderveld continues. They are exchanged “like the many coins of our inflated economic system.” A cliché should be seen “as a specimen of human expression which has lost much of its original ingenuity and semantic power, but gained in social functionality.”

Zijderveld saw a strong affinity between clichés and modernity. In my doctoral dissertation I took this though a step further: If Zijderveld is right then stereotypical thinking is a twin of the Zeitgeist, which also does not allow for any relativizations. The Zeitgeist shares a property Zijderveld attributes to clichés: “They become tyrannical in that stereotypes are hard to avoid in a fully modernized society; they are prone to become the molds of consciousness, while their functionality penetrates deeply into the fabric of socio-cultural and political life.”

To be sure, Vietnam was not the topic of my dissertation, with which I refuted the widely held stereotype that Martin Luther had paved the way for Adolf Hitler. I did this by pointing to large number of relativizing factors disproving this contemptible slander. In the present book, however, I am attempting something similar concerning Vietnam, though not in a scholarly manner but just by relating my personal experiences and observations.

Forty years after the communist conquest of Saigon, a stereotypical lump lies heavily on peoples collective consciousness: the absurd cliché that this victory, which was accomplished by means of torture and mass murder, was actually an act of liberation and thus a good thing. In its tyrannical way, as Zijderveld would say, this cliché allowed for no relativizing factors of the kind I describe graphically in order to counter a historical lie.

To remind my readers and myself that this is ultimately a book about a tragic war that ended in defeat for the victims of aggression, I will insert a brief reflection underscoring this fact every few chapters, beginning with a description of a mass murder the Communists committed during the 1968 Têt Offensive.

I owe gratitude to many people, but especially to my faithful friends Quy and Jo who steadfastly stood behind me as I wrote this book giving me every conceivable support while I labored over the manuscript. Every time I had finished a chapter, Quy translated it immediately into elegant Vietnamese with the help of his friend Nguyen Hien. He did the layout, designed the cover and gave me sound advice on cultural and historical questions. I am proud to have become part of Quy’s and Jo’s very traditional Vietnamese family in Orange County. I thank Quy’s brother-in- law, Di Ton That, and his wife, Tran, who were the first to contact me when I moved to southern California, and who introduced me to the huge and thriving Vietnamese community in Orange County.

I am grateful to the absent Đức, and to the countless other Vietnamese, American, French, British and German friends I made in Vietnam. I also wish to thank the Vietnam veterans whom I served as a chaplain intern at the VA Medical Center in St. Cloud, Minnesota, and the psychologists and ministers with whom I worked in order to provide those former soldiers with pastoral care. I am very thankful to my friend Perry Kretz for allowing me to publish some of his magnificent photographs from our reporting trip to Vietnam in 1972 in this volume.

I thank my friend and editor Peggy Strong and, most importantly, my wife Gillian who in our 50 years of marriage has stood by me and endured our long periods of separation caused by my assignment to an enchanting war-torn country I have come to love.

Uwe Siemon-Netto LagunaWoods, Calififornia

January 2015

Loading